PREVIOUS

Diversion of temple funds

July 31 , 2025

12 hrs 0 min

109

0

- Recently, a political controversy erupted in Tamil Nadu on the issue of diverting temple funds for building colleges.

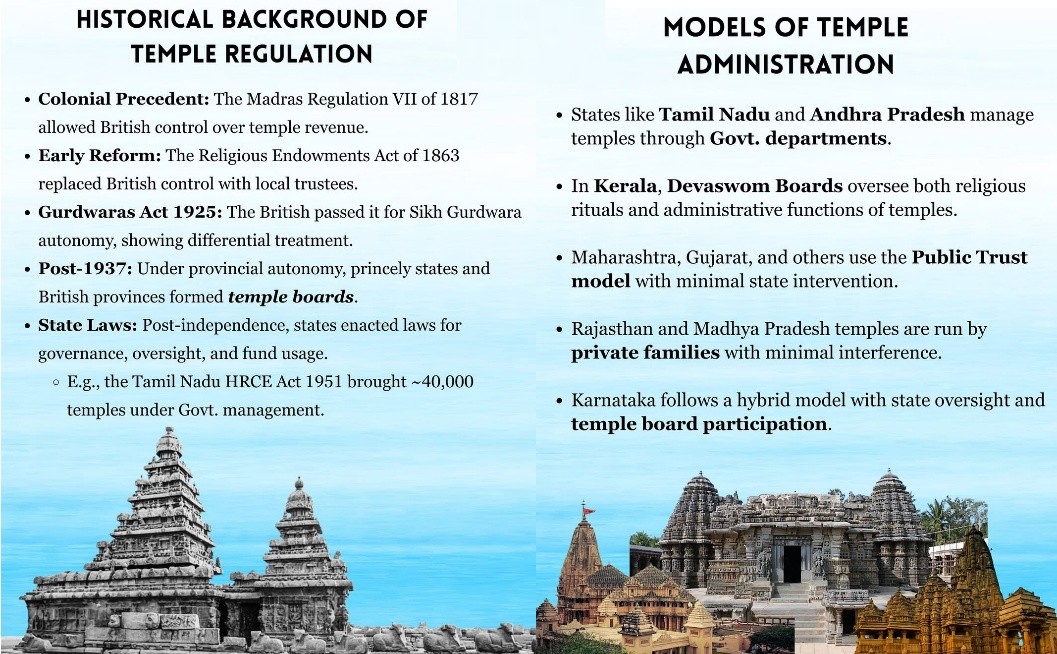

- This model, predominantly developed in the erstwhile Madras Presidency, draws strength from a 200-year-old legislative framework that continues to date.

- It has gained more acceptance in South India.

- Through the Religious Endowment and Escheats Regulation 1817, the East India Company set up the earliest legislative architecture around the regulation of the religious endowments.

- When the British Crown assumed direct control over Indian territories in 1858, Queen Victoria issued a proclamation stating that the sovereign would restrict interference in religious affairs.

- The idea of the government supervising religious institutions came to be crystallised when the Justice Party was elected in 1920.

- One of the earliest legislative interventions by the Justices was ‘Bill No. 12 of 1922: the Hindu Religious Endowments Act’.

- The issue was whether funds provided to a temple could be used for secular purposes.

- The matter was debated and settled in 1925, when the law was enacted.

- The current law is the Tamil Nadu Hindu Religious and Charitable Endowments Act, 1959.

- It has retained the provision of surplus funds.

- The Section 36 of the 1959 Act permits the trustees of the religious institutions to appropriate any surplus funds for any purposes listed under the law, with the prior sanction of the Commissioner.

- Temples received lavish donations from the sovereign rulers from as far back as 970 AD, when the Chola empire was at its peak.

- Over the last century, the Self-Respect Movement, which emerged from the Madras Presidency, viewed the regulation of temples and oversight of their resources as a critical feature of anti-caste reforms.

- Without this, there would have been no temple entry legislation in 1936 and 1947.

- Today, Tamil Nadu and Kerala are among the few States where governments have appointed priests from the Backward classes after a prolonged legal struggle.

Leave a Reply

Your Comment is awaiting moderation.